Project Description

Said Adrus was born in 1958, in Kampala, Uganda, in what was known as ‘British East Africa’. This seemingly straightforward biographical detail contains many pointers to the artist’s practice. His family arrived as part of the British colonial project to import large amounts of South Asian labour to its East African possessions to assist with the building of the railways etc at the turn of the 20th century. Years later, in the early 1970s, Idi Amin was to dramatically ‘expel’ the descendents of these indentured labourers. This expulsion created large numbers of refugees and displaced peoples, a number of whom came to the UK. A number went to other countries. Within this sketchiest of outlines we can perceive a layering of conflicting identities for an artist, or a person, such as Adrus. Born in East Africa at a time when it was controlled by the British represents a coexisting, or a fractious colliding of British, Asian, African, identities, which were to be compounded by the sudden imposition of a largely unexpected refugee or displaced person status. As Adrus himself recounted “my own father had been part of the British Army in Kenya during the Second World War.” Such service, or selective “Britishness’ would ultimately count for little or nothing in the eyes of sceptical Britain, which viewed with suspicion and alarm the prospect of Amin’s exiles seeking to come to Britain.

This sense of history being a means by which present-day conditions and identities can be animated and explored is critical to our understanding of Adrus’s work. He gained a B.A. (Hons) in Fine Art from Nottingham Trent Polytechnic, studying there at the same time as Keith Piper. Keith Piper was by far the most prolific and accomplished figure of the ‘Black Art’ movement of the early 1980s. More than any other Black artist of his generation, it was his fiery brand of racially charged and assertive images and text that announced the arrival of a new generation of Black artists, a new type of Black artist. There were many things that were new and fresh and different about Piper’s work and the ways it seemed to be wholly in step with the more progressive and militant aspirations and sensibilities of Black Britain. Piper’s practice was characterised by what was, in a British context, a new attachment to social and political narratives. These narratives were expressed through the mechanisms of Pop Art, assemblage sculpture, mixed media and a variety of other aesthetic references. It’s not difficult to imagine Adrus coming under Piper’s formidable influence, as other art students (such as Donald Rodney) had done.

Adrus has lived, and continues to live, something of a fragmented life, dividing time between residencies and home in the UK and projects and home in Switzerland, (where he has family) and other countries of Europe. In this regard, the realties of his life in effect add layers of complexity to Adrus’s biography and it is these layers of complexity that provide the artist with such fertile material from which to draw, in the making of his work.

His earlier pieces tended to be two-dimensional and relied heavily on the use of image and text. The self-portrait “often mechanically reproduced as a ground on which to work“ was a recurring feature of this work. As such, the self-portrait was not so much a declaration of self, but more of questioning of self, or perhaps more accurately, a means of critiquing the ways in which society ‘labelled’ and brutalised those it regarded as ‘other’. Adrus’s work of the 1980s spoke out against racism, discrimination and the interplay between imposed identities and one’s sense of self.

In this his earlier work, he consistently discussed his political identity, and his previous status as a refugee. For him, the royal coat-of-arms, as it appears on the ‘British’ passport offers itself as a perplexing, mocking and ultimately offensive symbol. In turn, the British passport becomes an icon of the transparently racist restrictions placed on those Ugandan Asian peoples who found that the ‘British’ passports they held were effectively worthless in terms of allowing them unhindered entry into Britain.

In Portrait of Another Kind, Adrus presents the royal crest comprising the unicorn and the lion as having massive, disproportionate and debilitating bearing on his identity. Another of his pieces, The Labelled Story graphically illustrated the constantly changing names and labels that have historically been attached to non-European people in Britain. Each change of label, each newly introduced definition, each manifestation of the vagaries of political correctness – all these things seem to reinforce the precariousness of both individual and collective social and political status. As a sub-text, the painting also laments our inability to decisively name himself. Is he Black? Is he African? Is he Asian? Is he British? Is he Black British? The name-calling, the labelling seems to be inexhaustible. The Labelled Story consistently obliges the viewer to critically assess the credibility of his or her nationality label.

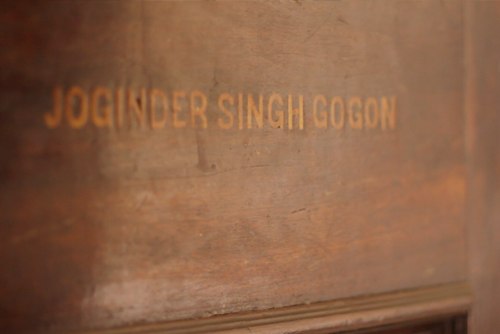

Over time, Adrus turned increasingly to mixed media, or multi-media, ways of working. Thus, the moving image, on screen and projection, became a central part of his gallery work. With ever-more sophisticated ways of presenting his work and ideas came ever more sophisticated ways of reading, and mining, his own history. Typical in this regard was Adrus’s recent work, which took as its starting point the Muslim Burial Ground in Woking, Surrey. The Muslim Burial Ground is a Grade II listed site located in a corner of Woking’s Horsell Common. Enclosed within ornate brick walls, the cemetery has a domed archway entrance reflecting the design of the nearby Shah Jehan Mosque, said to be Britain’s first purpose built mosque, established in 1889.

The Muslim Burial Ground was apparently built during the First World War to receive burials of Indian Army soldiers who, having fought and been wounded fighting for the British Empire, died at the dedicated hospital established for them in Brighton Pavilion. During the 1960s, the bodies of the fallen were exhumed and reinterred in the Military Cemetery at Brookwood, about 30 miles from London. According to Adrus, the work exists, in part at least, to highlight “issues about War, Empire, and Islamic Architecture in the South East of England and notions of contemporary landscape in the Home Counties.”

History is (the) key to us availing ourselves of the fullest understandings of this artists’ practice. The work assumes even greater levels of meaning and poignancy when we consider that, as mentioned earlier, Adrus’s “own father had been part of the British Army in Kenya during the Second World War.” Within this work, Adrus creates his own ‘memorial’ not just to the often forgotten and overlooked soldiers of the colonies who gave their lives fighting for the interests of this country, but also a memorial to history itself, and the multiple ways in which history impacts on our contemporary lives.

His website is www.saidadrus.com